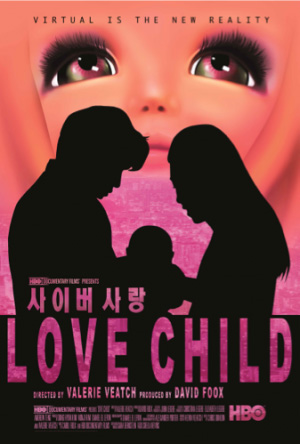

LOVE CHILD : Documentary

LOVE CHILD is a documentary film about Internet policy development. Centered in South Korea - the world's most wired nation - LOVE CHILD follows the story of the first case where "Internet addiction" was cited as a mental illness defense and looks at today's Korean gaming culture in search of harmony in an increasingly immersive media environment, where virtual is the new reality.

This was the official website for the movie.

Content is from the site's archived pages and other outside sources.

REVIEWS

The Internet’s Dark Side, Exposed

Three documentaries raise important questions about Internet use, from its effect on our personal relationships to our right to access information.

Three documentaries raise important questions about Internet use, from its effect on our personal relationships to our right to access information.

by Annie Minoff, on February 19, 2014

Love Child, directed by Valerie Veatch

Love Child, an HBO documentary set in South Korea, explores the impact of a headline-grabbing 2010 case in which an infant, Kim Sa-rang, died from neglect while her parents gamed at a local Internet café. (Ironically, the couple was raising a virtual child within the role-playing game they were addicted to.) The parents avoided serious jail time when their lawyer claimed in court that they were addicted to online gaming. They “were incapable of distinguishing between the virtual and the real” he says in the film.

“The story, to me, represented a distinct moment in human history where the divide between the real world and the virtual world collapsed,” Veatch told SciFri. Easy Internet access—due to an aggressive governmental campaign in the ‘90s to extend broadband access—is perhaps one reason why more and more South Koreans are living in a “mixed reality,” as one interviewee in the film describes it.

Sa-rang’s parents met inside of a game, and it’s also where they made money. “The internal economies [of these games] are real,” Veatch told SciFri. “You get to a dungeon! You meet a dragon! You need a sword! If you pay 20 cents to upgrade your sword, you can advance in the game.” Advanced players can make money selling items they’ve earned in games (such as swords) to less advanced players, a practice Koreans call “gold farming.”

Watching Love Child is an unnerving experience. Could this be a common scenario in the United States in 20 years? But for a filmmaker drawn to such a heartbreaking story, Veatch is surprisingly optimistic about our technological future. “It’s a problem today but it won’t always be a problem,” she said, citing efforts by the South Korean gaming industry to use games to also treat health problems. “I’m a total techno-utopian.”

A Documentary on Game Addiction Tragedy Fails to Press the Right Buttons

Scott Shackford | Jul. 29, 2014 3:35 pm

Last night HBO premiered Love Child, a documentary about a couple in South Korea who let their newborn child die of starvation in 2010 while they played online video games for hours on end in a PC café. The documentary gets its title from the name of the newborn—Sarang, which means "love" in Korean.

The documentary describes the couple's game-centric life and interviews the attorney who defended them, a worker at the game café they frequented, and the journalist who covered the tragedy and legal case for the Western media, among others.

The documentary is an odd duck in that it strives to avoid some well-worn media pitfalls that result in fear-mongering in the reporting of video game "addiction," yet its approach doesn't seem to delve into any sort of science or research, other than a look inside a Korean company that provides what seems like specious aversion therapy to gamers. Instead the film superficially drifts over the nature of South Korea's extremely high-tech, game-centric culture, pulling at little strings of ideas here and there without accomplishing much.

It's frustrating to watch as the documentary descends into babble about whether people who play a lot of games or spend a lot of time interacting through the Internet differentiate between the real world and a virtual world. This discussion seems to typically originate as fact-free musing from people about gamers rather than from the gamers themselves. Do people know they aren't actually ones and zeroes? Not sure what this means, but then again the documentary drifts between philosophy and absurdity. The chin-stroking takes a turn for the absurd when the documentary lets forth the suggestion that Sarang's parents didn't quite understand that babies need food to live because of all the time they spend in video games (the game in question, a now-defunct online role-playing game called Prius, involved taking care of a child-like assistant amid the adventures, and her existence is played up as much as possible to contrast with Sarang's neglect). Their defense attorney is partly responsible for pushing the "they didn't know how" narrative, so it makes sense for him to try to make the argument, but the documentary lets the nearly incomprehensible assertion just lie there all the way until the nearly the end, when somebody finally points out that people generally know that other people need food to live without special training.

In fact, the documentary reinforces the idea of gamer parents ignorant of the logistics of actual life by describing the communal nature of Korean society and suggesting the parents didn't have good relationships with their own parents (the family members themselves, though, are not interviewed for the documentary). South Korea's response to video game or Internet addiction has been government regulation—passing curfews to prohibit teenagers from playing video games after a certain time, reinforcing the idea that the problem is communal, not individual. Though there is a voice in the documentary stating that the problem isn't lack of regulation, his words become the segue to the exploration of the aversion therapy clinic. It's the equivalent of using drug addiction to promote drug courts. It doesn't really help illuminate anything.

The documentary floats over the basics of Korean culture like a travelogue on some lower tier cable channel without delving deeply enough to allow the viewer to understand what is really going on. Perhaps nobody really did, thus the long pauses for canned footage with ugly, multi-colored filters playing over junior college-level musings over the nature of the real world versus virtual reality. The documentary brings up the fact that the father was unemployed and was attempting to make money as a "gold farmer" in games. These are people who grind the drudgery of earning the online currency of games and then turn around and sell it for real money to other players so they can save time and purchase in-game goods without having to go through all the effort. But then this economic component of the couple's troubles is ignored. Why couldn't he find work? Was he unemployable because he was playing video games all the time, or was the order reversed? Did he end up playing video games because he couldn't find a job within Korea's information society?

Love Child clearly wants to make the viewer feel as though game addiction did ultimately cause Sarang's death. But the documentary doesn't want to appear to engage in fear-mongering, and yet it doesn't really do the hard work to make a valid case. The evidence remains circumstantial. A bunch of television news talking heads are shown referencing "Internet addiction," but given the media's reputation for mangling the results of scientific studies, it's not clear what we're supposed to take away from these invocations. It looks almost like Love Child wants it both ways—to engage in Internet addiction fear-mongering but in a fashion that appears sober and reflective and therefore not subject to the same criticism.

It's a shame, because it's not as though these isolated incidences aren't worth deeper analysis. I've seen lives destroyed by obsessions with gaming just as I have with drugs. But there's nothing actually useful about Love Child. It nibbles around the edges of a messy situation, afraid to get its hands truly dirty, perhaps out of fear of undercutting its own debate over the real vs. the virtual.

A KOREAN COUPLE LET A BABY DIE WHILE THEY PLAYED A VIDEO GAME

BY SEAN ELDER ON 7/27/14 Newsweek

Children die every day and it’s seldom front-page news; even the daily body count of Palestinian children being killed by Israel in the current conflict has produced the yaddaa-yadda effect in a lot of readers and watchers of news. 'Didn’t I hear this story yesterday?' they ask, reaching for the remote. But when a child dies because of parental neglect, the story has the ability to upend society, at least for a moment. Valerie Veatch was in Rome in 2010 when she saw a story on CNN International about a Korean baby who had starved to death while his parents were playing a video game. “My previous film was concerned with how technology impacts society, how we are changing, how we form relationships,” she says, referring to the 2012 Me @ the Zoo (which she co-directed with Chris Moukarbel), a film about a transgendered man and his life on YouTube. The Korean case was the only known one at the time in which a child had died as an indirect result of Internet gaming (an Oklahoma couple has since been accused of something similar). But the death of the three-month old Sarang (whose name means “love” in Korean) said as much about that country’s culture, old and new, as it did about the nature of addiction.

The resulting film, Love Child (HBO, Monday, July 28) premiered in Korea in the shadow of another, much larger tragedy: In April, a ferry bound for the island of Jeju capsized, killing over 300 people, many of them children on a holiday. (The captain and crew abandoned the drowning passengers and one member of the family that owned the ferry has killed himself.) “Parenthood has a sacred place in Korean society,” says Veatch. “All these parents were saying, ‘We’re poor and all our kids took the ferry, most rich kids get to fly over to the island they were going to.’ [The news] just started this self-reflective look -- what are we doing here? As a society we’ve grown so fast.’ South Korea had the lowest GDP in the world 50 years ago and now they are one of the main financial powerhouses in global economy.”

With that economic growth came quantum leaps in Internet connectivity. Love Child (which owes a lot to the reporting of Andrew Salmon, who broke the story on CNN and is one of the film’s talking heads) charts the government’s investment, starting in the 1990’s, in a broadband, high-speed internet structure and the business -- and gaming -- that followed. But most Koreans could still not afford the connection and a chain of popular video gaming parlors (“PC bangs”) sprung up across the land, serving the 24/7 needs of the millions of multiplayer game enthusiasts.The parents of Sarang met online, playing a popular (and since defunct) game called Prius. Little is revealed about them in the film except that they were poor, uneducated and that there was a big spread in their ages (he was 41 at the time of their daughter’s death, and the mother was almost 20 years younger). They created avatars (choices included robots, knights and wizards, with the option to customize your character) and soon set out on the game’s ultimate quest: to raise a virtual child. “If you complete the quest you are also given an Anima,” one of the gaming kids interviewed in the film explains. “The Anima is the central key to this game,” he says -- its personality changes depending on its interactions with the player’s avatar. Kind of like having a real child.

“I had heard they were raising an Internet fairy baby,” says Veatch, who got a crash course in Korean culture as well as the online gaming world from a number of filmmakers (and gamers) there. “I had no idea that the game kind of weirdly mirrored the story I was set on, or that it’s built into the game that the fairy baby dies.”

Anima (as the fairy baby was called) is a pixilated little Tinkerbell with big Keane-painting eyes. In one of Prius’s strange plot points, the baby -- which grows and bonds with the player’s avatar -- can sacrifice itself for you. You could watch her die on-screen, her big eyes crying blood, until she reappears as a butterfly and says, “If you earn enough experience points, you can revive me!” “Back around that time a lot of Korean games were coming out with these pet creatures you needed to take care of,” says Veatch, “and that was intentionally to bring in a bigger female base. Psychologically there is something about nurturing that they found would be engaging to a female audience.”

Real nurturing, however, was something Sarang’s parents knew nothing about. The mother only went to a doctor once before delivery and then returned to gaming almost immediately, though they claimed later it was for financial reasons. (Skilled players can barter their virtual money for real dough in what’s known as “Gold Farming.”) “They were unaware what they’d been doing, had no information about raising children,” says Salmon.

“The saddest thing about the story is that they weren’t bad parents,” says Veatch; “they just applied the parenting skills they learned from raising this Anima to raising this baby: feed it, game for ten hours, come back, feed it.... And the baby lacked the interface to communicate with them what it needs; it didn’t have display buttons on it that said, more this! They didn’t know how to read the needs of their baby because they could only read an online environment.”In the wake on Sarang’s death and the parents’ trial (the father served a year, the mother’s sentence was suspended) Korea came to face its internet gaming problem. Laws were passed meant to keep minors offline, or at least out of the gaming parlors, from midnight to six a.m. But far more intriguing than the legal possibilities raised by the case is the research Veatch did into one of Korea’s ancient cultures: shamanist religion.

There are scenes of modern Koreans, most of whom are Christian or Buddhist, taking part in ceremonies, banging drums and chanting, while a shaman leads them in one of the world’s oldest known languages. The shaman is the interface between the normal world and the spiritual world, we learn. “They are each possessed by a certain spirit and that spirit can guide them into the spirit world,” according to Salmon “There is a very immediate spiritual world you can travel to through these emissaries,” says Veatch. “I think that mentality is one reasons virtual gaming is so appealing in Korea. There is this sense of the spiritual and traveling into this virtual space is exactly the same as being present and not present.”

We learn at the film’s end that the couple has since had another child and given up gaming. The director does not overreach in her message and most of the story is left to the witnesses to tell. “It’s a basic responsibility as a human being to feed her own baby,” says the medical examiner, still reeling from the Sarang’s death years later. “It’s not something to be taught.”

More Background on LoveChildMovie.com

LoveChildMovie.com serves as the official website for the documentary film "Love Child," directed by Valerie Veatch. This compelling documentary, which premiered at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival, explores the complex intersection of technology, addiction, and parental responsibility in South Korea, widely regarded as one of the most wired nations in the world.

The Documentary's Premise

"Love Child" centers around a tragic incident that occurred in South Korea in 2010. The film examines the case of a couple who became so engrossed in online gaming that they neglected their infant daughter, resulting in her death from malnutrition. This heartbreaking event sparked a national conversation about internet addiction and its potential consequences on family life and societal norms. The documentary uses this incident as a starting point to delve deeper into South Korea's gaming culture, exploring how the country's rapid technological advancement has influenced social behaviors and relationships. It raises important questions about the blurring lines between virtual and real-world experiences, especially in a society where digital connectivity is deeply ingrained in daily life.

Critical Reception and Impact

Upon its release, "Love Child" garnered significant attention from film critics and technology commentators alike. The documentary was praised for its nuanced approach to a complex and sensitive topic. Many reviewers appreciated how the film avoided sensationalism, instead opting for a thoughtful examination of the societal factors that contributed to the tragedy. The New York Times described the documentary as "a chilling and illuminating look at Internet addiction." The review highlighted how the film effectively portrayed the pervasive nature of online gaming in South Korea and its potential to consume lives. Variety commended the documentary for its "measured approach to a hot-button topic," noting that it successfully balanced the specific case study with broader insights into South Korean culture and the global implications of internet addiction.

Cultural and Social Significance

"Love Child" holds significant cultural and social importance, both within South Korea and internationally. The documentary sheds light on several key aspects of contemporary society:

- Internet Addiction: The film brings attention to the growing concern of internet and gaming addiction, particularly in highly connected societies. It prompts viewers to consider the potential negative impacts of excessive online engagement.

- Technological Progress and Social Change: By focusing on South Korea, a country that has undergone rapid technological advancement, the documentary illustrates how societal norms and behaviors can be dramatically altered by digital innovation.

- Parental Responsibility in the Digital Age: The tragic case at the center of the film raises important questions about how parental duties and childcare practices are evolving in an increasingly digital world.

- Legal and Ethical Implications: The documentary explores how the legal system grapples with cases involving internet addiction, setting a precedent for how such issues might be addressed in the future.

The Website's Role

LoveChildMovie.com serves as a central hub for information about the documentary. While the website itself is not the focus of the film, it plays a crucial role in disseminating information about "Love Child" and its themes. The site typically includes:

- Synopsis and Trailer: Providing visitors with an overview of the documentary's content and style.

- Screening Information: Details about where and when the film can be viewed, including festival appearances and broadcast dates.

- Press and Media Coverage: A collection of reviews, interviews, and articles related to the documentary.

- Background Information: Additional context about the issues explored in the film, such as internet addiction and South Korean gaming culture.

- Resources: Links to organizations and services related to internet addiction and responsible technology use.

Audience and Reach

The primary audience for LoveChildMovie.com includes:

- Documentary Enthusiasts: Those interested in thought-provoking, socially relevant documentaries.

- Technology and Society Researchers: Academics and professionals studying the impact of technology on human behavior and social structures.

- Mental Health Professionals: Individuals working in fields related to addiction and family counseling.

- Policy Makers: Those involved in crafting legislation related to technology use and child welfare.

- General Public: People interested in understanding the complex relationship between technology and society.

Impact on Public Discourse

The website, by extension of the documentary it represents, has contributed to public discourse on several important topics:

- Digital Wellbeing: It has sparked conversations about maintaining a healthy balance between online and offline life.

- Parenting in the Digital Age: The site has become a reference point for discussions about how to navigate parenting responsibilities in a highly connected world.

- Cultural Differences in Technology Adoption: By focusing on South Korea, the documentary and its website highlight how different cultures may experience and adapt to technological change in unique ways.

- Gaming Industry Ethics: The film's exploration of addictive game design has prompted discussions about ethical practices within the gaming industry.

Educational Value

Many educators have found LoveChildMovie.com to be a valuable resource for classroom discussions. The documentary and accompanying materials on the website provide a starting point for exploring various topics, including:

- Media literacy and critical thinking about technology use

- Cross-cultural studies of technology adoption

- Ethics in game design and internet services

- The psychology of addiction, particularly in relation to digital media

- The societal impacts of rapid technological change

Continued Relevance

Although the documentary was released in 2014, the issues it explores remain highly relevant. As technology continues to advance and integrate further into our daily lives, the questions raised by "Love Child" about the balance between digital engagement and real-world responsibilities persist. The website continues to serve as a touchpoint for ongoing discussions about internet addiction, responsible technology use, and the evolving nature of human relationships in the digital age. It stands as a testament to the enduring impact of thoughtful documentary filmmaking in shaping public understanding of complex societal issues. LoveChildMovie.com represents more than just a promotional tool for a documentary. It serves as a digital gateway to a broader conversation about technology's role in modern society, inviting viewers to reflect on their own relationship with the digital world and consider the potential consequences of unchecked technological immersion.